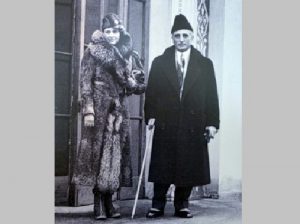

You can’t make this stuff up. The Trump Organization uses (and his trademarked) a coat of arms that was granted by British authorities in 1939 to former American Ambassador to the Soviet Union Joseph E. Davies, The New York Times reports today.

“There is one historical parallel between the Mr. Trump and Mr. Davies,” writes The Times’ Danny Hakim, who notes that Trump’s lavish Mar-a-Lago resort was built by Davies’ then-wife, Marjorie Merriwether Post. “Both men were controversially pro-Russian. Mr. Davies, who played an important role as a go-between for President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Soviets, has been criticized for being taken in by Stalin’s propaganda machine.”

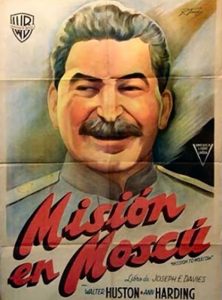

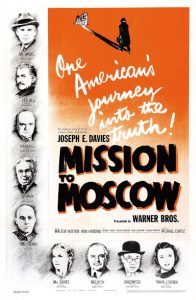

My longtime readers know that’s something of an understatement. Three-quarters of a century before Trump cozied up to Vladimir Putin, Roosevelt embraced another Soviet dictator — and Hollywood was more than happy to help out by selling Joseph Stalin to a skeptical American public. The most remarkable product of Washington and Tinseltown’s (temporary) celebration of the Soviet Union and its genocidal leader is “Mission to Moscow.” This jaw-dropping, lavish production (reportedly costing $2 million) is essentially a two-hour compendium of what Trump spokeswoman Kellyann Conway famously dubbed “alternative facts’’ about Stalin. With an investigation into whether Putin helped Trump win the presidency picking up steam, to call “Mission to Moscow’’ timely may be an understatement.

Of course, World War II was raging and there were sound strategic reasons for Roosevelt’s embrace of Stalin. Not a few military historians believe that tying up a substantial portion of Hitler’s armies on the Soviet front provided the margin of victory for allied forces over an over-extended Germany in Europe. And there was a legitimate fear that Stalin could forge another truce with Hitler, even if Hitler had broached an earlier non-aggression pact between the nations, forcing the USSR into World War II.

Screenwriter Howard Koch, who ended up blacklisted because of his reluctant participation, writes in his memoirs that the brothers Jack and Harry Warner both told him that Roosevelt personally asked them to film “Mission to Moscow.’’ It had been a best-selling memoir by Davies, who was FDR’s ambassador in the pre-war period and a Soviet apologist par excellence. Testifying before the House Un-American Activities Committee after Roosevelt’s death, Jack Warner repeated this claim but later recanted. Some historians believe the approach may have actually made through Roosevelt administration’s propaganda arm, the Office of War Information. But there is documentation that even during a war, the president found the time to meet with his longtime pal Davies on at least three occasions to be briefed on the film’s progress.

Screenwriter Howard Koch, who ended up blacklisted because of his reluctant participation, writes in his memoirs that the brothers Jack and Harry Warner both told him that Roosevelt personally asked them to film “Mission to Moscow.’’ It had been a best-selling memoir by Davies, who was FDR’s ambassador in the pre-war period and a Soviet apologist par excellence. Testifying before the House Un-American Activities Committee after Roosevelt’s death, Jack Warner repeated this claim but later recanted. Some historians believe the approach may have actually made through Roosevelt administration’s propaganda arm, the Office of War Information. But there is documentation that even during a war, the president found the time to meet with his longtime pal Davies on at least three occasions to be briefed on the film’s progress.

Directed by Michael Curtiz (“Casablanca’’’) with his usual panache and containing copious quantities of Soviet-provided archival footage expertly assembled by future Clint Eastwood directorial mentor Don Siegel, “Mission to Moscow’’ presents a hugely flattering portrait of a prosperous and happy Russia that’s at odds with most accounts by foreign visitors of the era. But the film more insidiously steamrollers history, providing tortured rationalizations for the non-aggression pact (to buy the USSR more time to build up its defenses against Hitler) and the USSR’s invasion of Finland (to protect it from the Nazis).

Davies — who was given unprecedented control over the film — wasn’t satisfied with these lies. At his insistence, the film makes claims that do not appear in his memoirs, most notably excusing the purge trials of Stalin’s political enemies. In the film’s highly fictional retelling, they were all secretly spying on behalf of Germany and Japan! Davies, played in the film by Oscar winner Walter Huston (who had portrayed Abraham Lincoln under D.W. Griffith’s direction) declares that based on his experience as a trial lawyer, the defendants’ “confessions” are credible. In another scene with chilling contemporary relevance, Davies defends the Soviets when a surveillance device is found inside the U.S. embassy. (“We have no secrets’’).

“Mission to Moscow” producer Robert Buckner (who had willfully distorted American history for entertainment purposes in the Errol Flynn vehicle “Santa Fe Trail’’) later later labeled the film (which co-starred Ann Harding as his wife, referred to only as Marjorie) “an expedient lie for political purposes, glossily covering up important facts with full or partial knowledge of their false presentation.’’

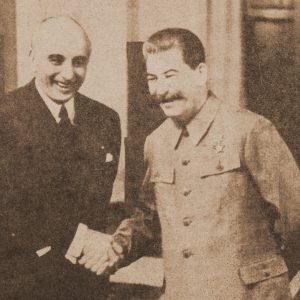

Small wonder that “Mission to Moscow” was the first Hollywood film to get an official showing in the Kremlin — Davies was in attendance — and that Stalin even reopened the Soviet market to U.S. movies for the first time in decades, at least until the Cold War began a couple of years later.

“Three days after viewing it, the Siren still feels as though somebody rewired her brain,’’ wrote my friend Farran Smith Nehme (aka the Self-Styled Siren) after her first viewing on TCM, in 2009. We ultimately programmed “Shadows of Russia,’’ an entire series of films built around “Mission to Moscow,’’ that aired on the network in 2010. (It’s available on DVD from the Warner Archive Collection).

I’ve introduced screenings of “Mission to Moscow’’ at both the Museum of the Moving Image and the Brooklyn Academy of Music (the second with a panel discussion). On both occasions, there were audible gasps from the audience during a scene where Davies meets briefly with a warm and cuddly Stalin (character actor Manart Kippen, billed only on some posters), who the film consistently portrays as a progressive whose goals are compatible with American democracy. This is when the ambassador tells the dictator, “Mr. Stalin, I believe history will record you as a great builder for the benefit of mankind.’’

Of course, in the real world, exactly the opposite is true. Because of its talkiness and heavy-handed propaganda, “Mission to Moscow’’ has infrequently been seen since its theatrical release in the spring of 1943, a fascinating historical curiosity. But thanks to the new administration in Washington, it’s acquired a totally unexpected timeliness, even if it seems unlikely that present-day Hollywood will indulge President Trump’s mysterious desire to burnish Putin’s image. Then again, few would have predicted a Russia-loving Republican president could be elected a year ago.

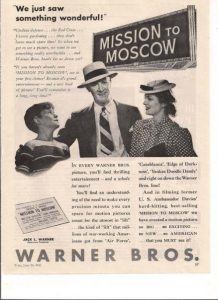

I’ve written two much longer pieces on the fascinating history of “Mission to Moscow,’’ one for the now-inactive Moving Image Source and another for the New York Post. “Mission to Moscow’’ was backed by an extensive promotional campaign, including this remarkable 30-page press book that my colleague Gregory Miller posted to Tumblr on my behalf a few years ago.

The New York Times reports that British authorities wouldn’t allow Trump’s properties in Scotland to use the Davies coat-of-arms that is displayed at his U.S. courses (with the word “Integratas” — Latin for “integrity” — replaced by Trump). And that Davies’ descendants contemplated suing the future president few years ago but were dissuaded by his grandson, former U.S. Senator Joseph D. Tydings.

“The way he operates, you don’t sue Trump, because you’ll be in court for years and years and years.” Grandpa Joe Davies, Tydings told The Times, “would be rolling over in his grave to think he was using his crest.”