“Jerry Lewis is either terrific or terrible — he doesn’t have the option of being adequate,” says Jerry Lewis, warming to his favorite topic. “People either hate him, call him a megalomaniac and a moron, or they love him. I’ve never heard anybody say he’s a nice guy.” From time to time, Lewis turns from his interviewer to address one or another of the half-dozen aides who fill his spacious penthouse atop the Helmsley Palace. All of them respond overeagerly to every remotely funny remark by the boss. At one point, even Jerry’s dog wanders into the suite to bark approval.

Love Lewis or hate him, the man is an institution, New Jersey’s second most illustrious (after his good friend Frank Sinatra) contribution to show business. Born Joseph Levitch to a pair of Newark troupers, Lewis was lip-synching records on stage at the old Central Theater in Passaic before he was out of his teens. That was in 1943, three years before his swift ascent to the top in tandem with a laid-back baritone named Dean Martin (nee Dino Crocetti).

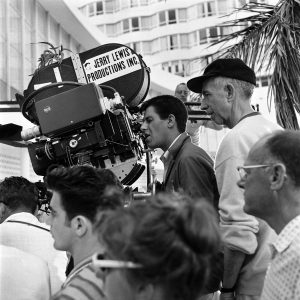

Even in this superstar era, the figures remain impressive. Martin and Lewis were Top 10 box office movie stars from 1950 until their acrimonious split in 1958; Lewis alone continued as a major box-office attraction into the late 1960’s. He has appeared in 45 films (total gross: $300 million) during the past 35 years, directing 14, producing and writing many.

During the last 10 years, though, America’s most aggressive clown has starred primarily in the pages of supermarket tabloids. He has declared bankruptcy, overcome an addiction to the painkiller Percodan, undergone open heart surgery, and divorced his wife of 36 years.

Of the six movies he’s appeared in during the decade, only two — “Hardly Working” and “King of Comedy” — received full-scale theatrical releases in this country. There are no U.S. takers so far for “To Catch a Cop,” Lewis’s first movie made in France, the country where he has long been revered as a successor to Chaplin and Keaton.

On this snowy afternoon in March, he is in Manhattan to promote another film, “Slapstick of Another Kind.” (At his press agent’s insistence, the interview is not to be printed until the movie’s release. As it turns out, “Slapstick” will never see the inside of local movie houses; it debuts tomorrow on Home Box Office.)

Impeccably dressed in a conservative blue suit, he speaks rapidly in a low voice only rarely punctuated by his verbal trademark, a high-pitched, raucous laugh. With his jet-black hair and unlined face, Lewis looks nearly two decades younger than his 58 years. The years of struggle are betrayed only by his cold gray eyes — the same eyes that mirrored the occupational ennui afflicting Jerry Langford, the talk-show host he played in “King of Comedy.” During a wide-ranging, two-hour conversation studded with profanity, Lewis charts, sometimes with rancor, the recent downward curve of his film career. He eagerly renews his running war with American film critics, who have invariably dismissed his efforts as sophomoric.

When he isn’t lurching in a somewhat manic way from insufferable egotism to maudlin self-effacement, Lewis enthuses over his upcoming schedule. It would give pause to a man half his age, let alone one who suffered a major heart attack just two years ago.

In the six months since our talk, Lewis has (1) completed a second French film in Algeria; (2) hosted a one-week trial run for a syndicated TV talk show that may lead to a regular series early next year; (3) played Atlantic City for a week; and (4) nearly completed the script for “Nutty Professor II,” a follow-up to his classic 1963 Jekyll-Hyde comedy. He hopes to begin shooting the movie this fall.

For the last month, Jerry’s been at his home in Las Vegas — where he lives with his new wife, 32-year-old SanDee — preparing for his 18th annual telethon for the Muscular Dystrophy Association. Lewis will begin his 21 1/2-hour ordeal tonight at 9 on Channel 5.

Following are excerpts from the interview:

You titled one of your books “The Total Filmmaker,” yet why were three of your last four films directed by others?

If you directed all the time you’d need a rubber room. The role of the director is probably the most arduous job in the world and when I work on a script, whether I write it or not, I break it down for nine months. I don’t roll a camera until I have everything nailed down. Then, I do that homework all over again every day. I used to work 28 hours out of every 24. Since the surgery, I get everything done in a 15-hour day and I’m very satisfied.

How else has your life changed since your heart attack?

After three months, the doctors let me do three days onstage. That was a little scary, because you get crazy physically and you think that all of the stitches are going to come loose.

I feel marvelous, considering the alternative. (Emits his trademark laugh.) God almighty, I walk on the Carson show, and he says, “a grown man and you’re still taking money for making noises and silly voices.” Then I give him regards from Sinatra and thank Johnny for getting us off the . . . cover of [a well-known supermarket tabloid]. When my attorneys were filing a lawsuit against them, their attorneys told mine, “Whenever we have a slump in circulation, we put Sinatra or Jerry on the cover and it comes way up.” So I called them up and told them, instead of making up [stories] call me up. Some of my [stories] play better.

There have been reports you’re moving to France.

No, I’m not going to leave my country, though I do spend a lot of time in France. I bought some land there 15 years ago, and when [French President Francois] Mitterand presented me with the Legion of Honor earlier this year, he mentioned that I am a landowner. From there someone surmised that Jerry was going to move.

What’s your French film like?

It’s called “To Catch a Cop,” and it’s cute. In France or anywhere in Europe, you can play an almost-straight role and it’ll work comically for you. I’m a cop, Michel Blanc is a cop, the whole theme of the picture is that everybody’s a cop. Everybody’s chasing everybody.

Do you speak French in the film?

(He affects a broad Gallic accent.) But of course. All you have to do is say “ze” and “zat.” Why did you choose to do “Slapstick,” an adaptation of a Kurt Vonnegut novel?

While I was paid a lot of money, I mostly did it because the director, Steven Paul, had a dream. This kid was in my office annoying me for eight years, since he was 17 years old. He got the option on the book predicated on getting me. I couldn’t walk away from that. I’m doing interviews to sell the picture, but I’m outrageously honest. And I have to tell you it misses. It’s a shame, because this is as close as Vonnegut will ever get to getting his work on the screen. I helped Steven as much as I could technically, but I would never have accepted this film as a directorial assignment. It’s just too weird, not my kind of comedy, really.

Why did Warner Bros. sell another of your films, “Smorgasbord,” directly to cable TV?

My mistake was making the picture for a little more than $4 million. Warners knew it wasn’t a megabuck movie, so they weren’t going to put $3 million in prints and advertising. You put your life’s blood into a theatrical, and without your permission, they made $12 million just putting it on cable and cassettes. I call that . . . dirty pool and I’m going to sue {them}.

It’s interesting that during the entire period, from the coming of talkies to the decline of the studio system in the 1960’s, you were the only comedian who managed to take control of his films as a producer-director.

I had to, only because I wanted to take the autonomy out of the hands of the incompetents. It wasn’t so much for the power, but to make sure that if they wanted a film to be adjusted — say, to have 12 minutes cut — they should let me make the cuts.

Do you consider “The Nutty Professor” [1963] your best film?

I think so; from the writing to the directing to the acting to the producing, for me it was the total work. You only have to do one of those in your career. But I’d like to take a shot at doing it a little better, so that’s why I’m making a sequel.

Many people have assumed that Buddy Love — the womanizing, obnoxious alter ego of the shy, awkward Prof. Julius Kelp — was your way of getting back at Dean Martin. Is this so, is the character based on him?

No way. Buddy was a conglomeration of the bigot, the snob, the heckler in an audience, the Joe McCarthy of the theatrical world. Because he was suave, tall, and good-looking, some people identified him with my ex-partner. But I love my partner. I would never have written that with him in mind.

Are you friends with Dean? Do you ever speak?

We don’t socialize, we don’t seek each other out, but when we are brought together there are great moments of reminiscence. We last saw each other two years ago at the Golden Globe Awards. Someone brought us a reunion project a few years ago, but it didn’t work out. One thing I’ve learned in this business is you never say never.

What do you consider your worst work?

I’ve got a list that would take a half-hour. For all the wrong reasons: sometimes a feeling of insecurity, sometimes not feeling well. If a dramatic actor’s baby is sick in the morning, he can turn that into a performance. You tell a comic that and he doesn’t go to work.

Why do you think you’re so much more popular in Europe?

The Martin and Lewis pictures would gross around $2 million there. But a Jerry Lewis film would start at a $5.5 million gross, because he directed it. That’s the way they think.

Moving away from the relatively complicated plots and verbal humor of the Martin-Lewis pictures to a more visually oriented style wouldn’t seem to have hurt.

Plot is the disease that will eat away at the basically simple fun. It’s important, but when it begins to infringe on the humor, it’ll begin to put your funnybone to sleep.

To this day, I wish someone would tell me what Blanche DuBois was yelling about in “A Streetcar Named Desire.” When I first met Tennessee Williams, I told him, “You’ve given me a headache that’s run about 29 years,” and asked him to explain the play. “Jer,” he replied, “you wouldn’t understand if I told you.” I think most people are ashamed to admit they don’t understand something.

Are there any younger comedians working today you particularly respect?

Richard Pryor, Robin Williams, Woody Allen, and Charlie Callas, who should have been a big star. I saw a kid last night, Billy Crystal, in a nightclub here and he’s . . . brilliant.

What about Eddie Murphy?

You haven’t even see the tip of the iceberg. He’s got that innate Jewish comic tendency –I’m not being facetious, the Jewish among us that have it, have it from birth — in the black form. He’s got a sense of timing that’s incredible.

As a writer-director-star, in many ways you anticipated the work of Mel Brooks and Woody Allen. But unlike them, you’ve never played a definite ethnic character. Why have you continued to downplay your Jewishness on screen?

I never hid it, but I wouldn’t announce it and I wouldn’t exploit it. Plus the fact it had no room in the visual direction I was taking in my work.

What’s the status of “The Day the Clown Died” [1974], in which you played a clown in a World War II German concentration camp?

It’s still tied up legally in the vault in Sweden, along with two [Ingmar] Bergman films and a Louis Malle from the early 1970’s. But I’m fortunate that mine is a period picture. My attorney in London tells me there’s some progress.

Are you planning to play any more serious parts?

Hell, no! Not unless I get another script like “King of Comedy.” Were you gratified by the good reviews you got, virtually your first in this country?

What? (Mock astonishment.) From the critics? No! How can I keep telling them they’re morons and then when they write good about me, tell them they’re wonderful? None of us in the film industry really {cares} about getting ripped as long as the guy takes a look at our work and has a point of view. But a lot of reviews come straight from press brochures.

In your opinion, why are the critics are so hostile to you?

They’re prejudiced because I’ve ripped them. I’ve asked for it. But on the other hand, the critics have given me a longevity. The greatest thing that can happen to a young performer is for the critics to jump on him, so the public can defend him, embrace him. The difference between Martin and Lewis’s earning capacity — $8 million a year — and my personal earning capacity at present is only half.

I’ve had over 40 years as a star; that’s unheard of. George Burns is unique, he didn’t become a big name alone until he was 75. Bob Hope cannot be placed in the same category, he’s a national treasure. Other than that, you name for me someone who’s had a pretty consistent position for 40 years. I have had about 8 to 10 years longer in my career than I should have had; and it’s largely thanks to the critics. And my fans.

I’ve grown up with most of you young guys that were a part of my life and I was a part of your lives. Whether you like Jerry or not, the recollection is there. More than likely it’s a good one, because I portrayed you when you were 7 years old.