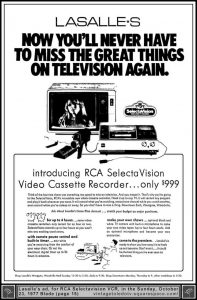

It’s 40 years since the first commercially viable VCR — RCA’s Selectavision, which caught on the with mass market in a way that Sony’s Betamax never did — went on sale. I bought RCA’s very first VCR in 1977, and wrote this remembrance in 1994, when the VHS format was still going strong. I had retired my original $1,000 machine (used so often that the heads were replaced three times) by this point, and finally tossed it in the trash a couple of years later. Here it is, as originally published in February 1994:

I was the first on my block to buy a VCR.

The year was 1977, and RCA had introduced what, to a lot of us, was

the first practical videocassette recorder.

Actually, back in those days practically everyone called them

Betamaxes, the way people call tissues Kleenexes. Sears had introduced a short-lived home video system called Cartrivision in 1972, but it was

Sony that created a sensation with the heavily advertised Betamax three

years later. Early models were built into consoles with 25-inch TV sets,

sold for upward of $3,000 — and could only record only 20 minutes at a time. Even when Sony upped that to an hour and introduced models that

could be hooked to existing TV sets, there were very few takers.

Then RCA entered the picture. It didn’t even make the machines

(Matsushita, which did, soon put out nearly identical ones with

Panasonic nameplates), and its VCRs provided picture quality that was,

truth be told, slightly inferior to that of the Betamax. But the big

enticement of the Video Home System — VHS, which went on to drive the

Beta system into virtual extinction — was its extending running time.

RCA’s first models could record up to 4 hours and 20 minutes at a pop,

enough for two to three movies.

And make no mistake about it, it was movies that fueled the VCR

revolution.

Contrary to marketers’ expectations, most people did not race out

and buy VCRs to tape their favorite soap operas or, say, “M*A*S*H” for

watching at a more convenient time.

They bought them to watch movies.

Take me. I gladly forked over $1,200 (list price) for the last

available machine at the Friendly Frost appliance store in Garden State

Plaza — three other places I called had instantly sold out that weekend

when RCA’s first model went on sale. It was an imposing chrome and

faux-wood-grain device with a manually operated channel changer and an

analog counter. It must have weighed 50 pounds. To record something, you

had to push down on piano-style keys. If you set the timer for the

middle of the night (which I often did), chances were you’d be awakened

by a loud click when it went on.

Though videotape was both expensive — about $20 a pop — and scarce

in those days, I quickly amassed a library. I had 50 movies on tape

within a month, 100 in 90 days. I lost count after 300. I was hardly

alone; a national videotape shortage occurred when CBS broadcast “Gone

With the Wind” for a second time in 1978.

It didn’t hurt that there was an awful lot of stuff out there to

tape, thanks to the burgeoning growth of cable television. Home Box

Office and Showtime quickly spun off sister services offering all-movie

diets: Cinemax and The Movie Channel. In the late Seventies, my cable

system not only offered round-the-clock movies from Ted Turner’s WTBS

superstation, but additional movies beamed in from Philadelphia, Boston,

and Worcester, Mass. Thanks to the miracle of microwave transmission, it

also beamed in a PBS affiliate in Wilkes-Barre, Pa., that showed

something like 60 movies a week. Within a three-year period, I wore out

two sets of recording heads on my VCR.

It wasn’t as if you could go out and buy “Gone With the Wind” — or

“Casablanca,” or almost anything else in the early years. Except for

20th Century Fox, which licensed 50 titles to an obscure Michigan outfit

called Magnetic Video in 1977, Hollywood wasn’t interested in selling

movies to the consumer, to say the least.

The idea of individuals’ owning copies of movies violated a concept

that went back to the beginning of the film industry. Even theaters only

rented them. But thanks to VCRs, people not only owned copies of movies,

they could acquire them without paying for them!

This idea was so threatening that the Walt Disney Co. and MCA

(parent company of Universal Studios) went to court against Sony,

maintaining that taping their movies — even for personal use —

constituted copyright infringement and theft.

U.S. District Judge Warren J. Ferguson thought otherwise.

In a decision with profound ramifications, he ruled in 1979 that

home taping was “a fair use of copyrighted works.”

Hollywood saw the handwriting on the wall. Rather than appeal, it

decided to join the revolution. All of the studios, including Disney and

Universal, set up video divisions.

I remember walking into a video store for the first time. It was

the old Video Shack on Route 4 in Paramus. There were so few titles

available that they were kept under glass. Except for the X-rated ones

in the back.

That quickly began to change. For one thing, nobody had foreseen

that a whole new industry would spring up around the rental of movies on

tape. After all, few people were going to run out and buy new movies,

which were going for $80 to $100 apiece in those days. Before long, you

could rent movies at the supermarket, or at the dry cleaner’s.

Theater owners were nervous. They saw home video as a competitor

that would keep their customers at home. They threatened to boycott when

Fox (which had bought Magnetic Video and renamed it Fox Video) decided

to release “9 to 5” within 90 days of concluding its theatrical

release. But just three years later, there was hardly a peep when

Paramount decided to issue “Flashdance” while the picture was still

playing in theaters.

What had happened in the interim was this: Rather than reducing

theatrical audiences, home video had actually whetted people’s appetites

for moviegoing. Theatrical admissions rose steadily throughout the

1980s. People who hadn’t been the movies in years liked what they saw on

tape or on cable TV and decided to check out what was in the theaters.

It didn’t hurt that the video market had fueled a worldwide film

production boom — in the mid-1980s, it was practically impossible to

lose money making a modestly budgeted movie — so there were a lot more

movies to choose from in theaters than there were in the late Seventies,

when even a dud might linger for a month or two.

I was a movie critic from 1981 to 1989, and from talking with my

readers, it was obvious they were becoming more interested in and more

sophisticated about movies. It was in this period that newspapers and

broadcasters started reporting box-office grosses as if they were sports

scores. Previously, nobody much cared outside of the business. And

thanks to the voracious appetites of cable TV and video for “software,”

movies that hadn’t seen the light of a cathode ray tube for decades —

silents, early talkies — were regularly on public display.

What video did was restore moviegoing as an American habit, in a way

it hadn’t been since the early 1950s. Once TV started force-feeding

movies to people in chopped up, adulterated form, interest waned. But

video enabled people to see what they wanted, when they wanted. Not

everybody thought this was great — I remember a girlfriend’s lament that

“The Wizard of Oz” was no longer an event when you could watch it on

demand (twice in a row, if you liked) instead of anticipating its annual

showings for 12 months. But a whole lot of us thought it was nifty.