The Museum of Modern Art is currently presenting “Son of Universal,’’ a sequel to last year’s series of new restorations by that studio of rare films from the late silent and early talkie era produced by Carl Laemmle Jr., many of which haven’t been seen in many decades.

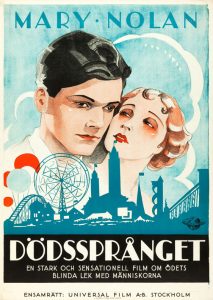

A couple of especially fascinating ones are being repeated this coming Sunday afternoon, May 14. They both star Mary Nolan, whose name didn’t ring a bell with me — though I recognized her face immediately from an iconic image in Kenneth Anger’s notorious (and often factually challenged) collection of vintage Tinseltown gossip, “Hollywood Babylon.’’

Nolan first rose to fame as a Ziegfeld girl who danced and sang under the name Imogen “Bubbles’’ Wilson. “Only two people in America would bring every reporter in New York to the docks to see them off,’’ columnist (and future film producer) Mark Hellinger wrote in 1922. “One is The President. The other is Imogene “Bubbles” Wilson.”

A stunningly beautiful blonde, Wilson was undone by her poor romantic choices. An involvement with a married vaudevillian snowballed into such a scandal that Ziegfeld fired her in 1925. She traveled to Germany, where she appeared in 18 silent films under her real name, Imogen Robertson.

She returned to the United States two years later under — rechristened Mary Nolan. Mostly, she was under contract to Universal Pictures, which loaned her out to MGM for her best known role — as Lionel Barrymore’s drug-addled daughter in Tod Browning’s sordid 1928 Lon Chaney vehicle “East of Zanzibar.’’

By this time, Nolan was the mistress of MGM executive Eddie Mannix. She later blamed a beating administered by Mannix for extensive surgeries and the morphine addiction that would end her film career.

The two films showing Sunday at MoMA, Lew Collins’ “Young Desire’’ and Tod Browning’s “Outside the Law’’ were both released in 1930, just before Universal dismissed the troubled Nolan, who was around 25, reportedly because she had become so difficult to work with. After that, she toiled on Poverty Row for a couple of years before that before hitting the vaudeville circuit. She died of an overdose at the age of 42.

In both the restored films, art imitates life with Nolan making poor choices in men. She’s a cooch dancer for a sleazy carnival under the thumb of sleazy boss Ralf Harolde in “Young Desire.’’ She decides to run away to Hollywood, but make it only as far as an orange grove where she is picked up by the owner’s son, a rich young college boy played William Janney.

He is so smitten by the beautiful Nolan that he puts her up in an apartment building owned by his father. Nolan writes to a pal at the circus that she plans to take her younger admirer for every cent he’s got, but she eventually succumbs to his lack of guile and the promise of a better life.

But then Harolde shows up like a bad penny, and the boy’s parents pleads with her not to ruin their son’s life and theirs. Let’s just say Nolan’s “Camille’’ like gesture — which involves a trapeze act on a balloon 100 feet in the air — drew gasps at the screening I attended.

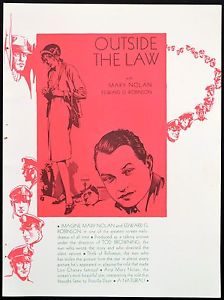

It’s a stunning performance and Nolan is almost as good in “Outside the Law,’’ which is a remake of Browning’s 1920 Lon Chaney vehicle. Though she again gets top billing, in the first half Nolan’s part is subsidiary to Owen Moore (the erstwhile Mr. Mary Pickford, who had his own substance abuse issues) as Fingers, clever bank robber she has unwisely hooked up with. Fingers has pulled off a half-million-dollar heist, but crime boss Cobra (Edward G. Robinson) demands a cut from Fingers, who has muscled in on his territory. (Chaney played both the male parts in 1920).

Nolan dominates the second half of the film, which takes place on Christmas Eve. She and Moore are nervously hiding out with the loot, and both of them are going stir crazy. Moore, a sentimental sort, befriends a child down the hall of their apartment building — and that brings out all sorts of feelings that the Nolan’s hardboiled character has been bottling up.

Things end badly for both of them, and even worse for Cobra. There’s a very strange final scene that suggest Nolan may have departed the film rather abruptly. But for all the contrivances, this and “Young Desire’’ reveal that Mary Nolan deserves a spot in the pre-code Hall of Fame alongside Dorothy Mackaill and Jeanne Eagels.

“Outside the Law’’ was restored primarily from an incomplete 35mm negative from Universal’s vaults. Two missing reels were filled in using a digital scan of a 16mm print held by Wesleyan University — and the difference is barely noticeable.

Another 16mm print, from the Library of Congress, was used as the sole source for Universal’s remarkable digital restoration of Lois Weber’s “Sensation Seekers’’ (1927). Silent star Billie Dove is terrific as a wild flapper who falls in love with a hunky young minister (Raymond Bloomer).

Writer-director Weber, who helmed only one minor talkie, expertly toggles between naturalistic romantic scenes and a wildly melodramatic climax at sea.

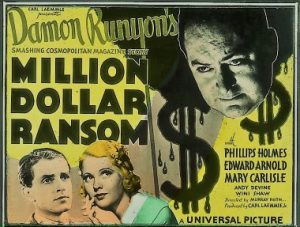

The series includes some interesting if little-seen films that Universal made after establishment of the Production Code Authority. Murray Roth’s “Million Dollar Ransom’’ (1934), which carries PCA certificate No. 93, is being repeated this Saturday, May 13. It’s an entertaining vehicle for character actor Edward Arnold, who stars as a former bootlegger who stages a fake kidnapping with fateful results in a gimmicky but fun story by Damon Runyon. Also repeating on Saturday is Roth’s “Don’t Bet On Love’’ (1933) stars Lew Ayres as a plumber with a gambling problem and Ginger Rogers (who’s surprisingly only in around a third of the 63-minute programmer) as his long-suffering girlfriend.

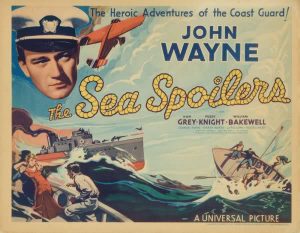

I also enjoyed Frank Strayer’s “Sea Spoilers’’ (1936), which apparently hasn’t been seen in New York since a week-long run on WOR’s “Million Dollar Movie’’ 54 years ago. In one of six non-western programmers that John Wayne made for Universal in the 1930s, Wayne stars as a brave Coast Guardsman who rescues his girlfriend (Nan Grey) and commanding officer (William Bakewell) from seal poachers with the help of Fuzzy Knight. The action-packed 63-minute film is enhanced by considerable location shooting.