Viewers should definitely fasten their seatbelts for the TCM premiere of “Myra Breckinridge’’ (Friday night June 28 at 2 am Eastern on “TCM Underground’’). This notorious and pioneering gender-bending oddity from nearly half a century ago is definitely a bumpy ride. But in my humble opinion it may be worth the trip at least once, though it’s certainly not for all tastes. It does offer dozens of classic movie clips and references, as well as appearances by a bunch of Hollywood old timers. And it explores sexual fluidity in ways that seem simultaneously very 21st century and creepily anachronistic.

It seems only fair to warn you up front that “Myra’’ is the first film from a major Hollywood studio in which a man is, well, anally raped. While some might consider this a spoiler (which I don’t think really applies to a 49-year-old movie where the pre-Disney Fox actually teased this extended sequence as “the most sensational scene in the history of the screen’’ in a trailers), I think it’s more like what we’d call a trigger warning these days.

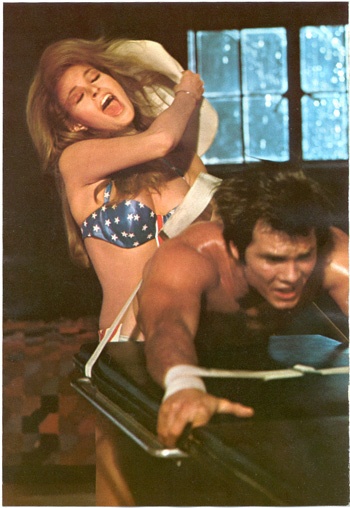

Some will undoubtedly be offended or at least unsettled that the involuntary pegging is portrayed as a sort of naughty trick played by a dildo-wearing, crypto-feminist transwoman (Raquel Welch in a campily committed performance that seems much more impressive after nearly half a century) out to “realign the sexes.” There are many homophobic, transphobic and misogynst slurs that were intended satirically by the author of the source bestseller, Gore Vidal, but don’t necessarily come off that way in the film.

Sad to say, the inexperienced director, Michael Sarne, is often not up to the challenge of steering this ship into port through Vidal’s often-blistering satire of classic and new Hollywood, not to mention pretentious film critics and the late ‘60s counter-culture. Lord knows, there are TCM viewers who will nod in agreement when Myra, paying homage to Marlene Dietrich in “Seven Sinners,’’ proclaims that “during the decade between 1935 and 1945, no unimportant film was made in the United States.’’

Sad to say, the inexperienced director, Michael Sarne, is often not up to the challenge of steering this ship into port through Vidal’s often-blistering satire of classic and new Hollywood, not to mention pretentious film critics and the late ‘60s counter-culture. Lord knows, there are TCM viewers who will nod in agreement when Myra, paying homage to Marlene Dietrich in “Seven Sinners,’’ proclaims that “during the decade between 1935 and 1945, no unimportant film was made in the United States.’’

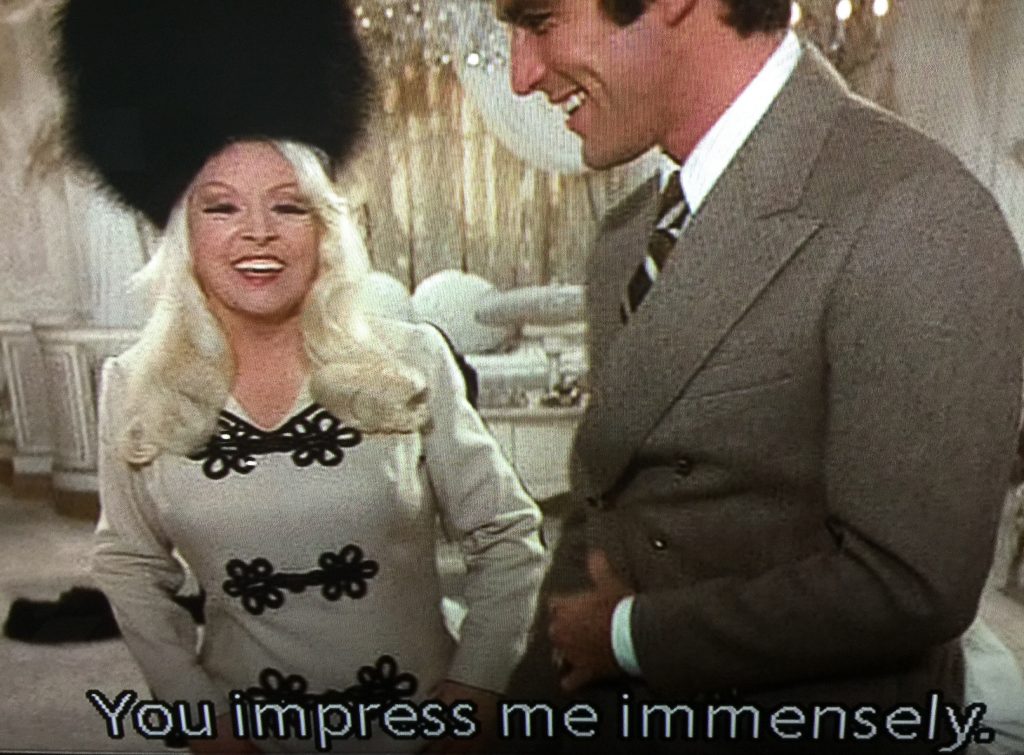

Probably not even George Cukor, who Rex Reed (stunt-cast as the pre-surgery Myra) claims was originally going to helm, could have actually directed screen icon Mae West. At the age of 76, she returned to the screen after a 27-year-absence (with top billing) to satirize her image as a sexually insatiable talent agent (whose conquests include Tom Selleck in his screen debut). She also performs two mind-blowingly awful musical numbers and has one brief over-the-shoulder exchange with Myra (West refused to appear in the same shot as the Welch, who was approximately 50 years younger than her at the time).

Second billing goes to a gung-ho John Huston, who hilariously embodies (in way too much footage) what we now call toxic masculinity as an aging former cowboy star running a fraudulent acting school in Westwood. He’s led to believe that self-described “dish’’ Myra is the widow of his nephew Myron. The flimsy main thread of the plot involves Myra trying to collect her half-interest in the property.

Third-billed Welch, a sex symbol cast against type as the lusty Myra, powers her way through the film’s many dead spots with highly stylized line readings and gestures while modeling some truly stunning Theadora Van Runkel costumes that nod to Hollywood’s Golden Age.

Myra’s leering machinations include not only humiliating and defiling one of her hunky male students (Roger Herren in a career-destroying role) but seducing his girlfriend (a positively dewy Farrah Fawcett in her screen debut). At one point, the woman whose poster would adorn dorm rooms all over America shares a bed with both Myron and Myra, but that’s actually pretty tame compared to the jaw-dropping scene where Myra performs fellatio on her alter ego.

Perhaps Sarne’s best idea (he didn’t have many) was commenting on, and in some cases punctuating, the action with clips from at least 50 movies, well-known and obscure, drawn almost entirely from the 1930s through the 1950s, all but one from the Fox archives. The most heavily sampled film is the Laurel and Hardy comedy “Great Guns’’ (1941). A list of the others in order of appearance is below if you’re interested.

“Myra Breckinridge’’ has historical interest as the first Hollywood film from a major studio to depict a transsexual character, albeit in a highly politically incorrect manner, arriving in New York a week before UA’s “The Christine Jorgensen Story.’’ Vidal makes the operation a sort-of surprise reveal at the end of his book, but the movie turns Myra letting her, um, hair down anti-climactic. The film actually opens with Myron (a young, handsome and bitchy Reed) eagerly awaiting his surgery at the hands of John Carradine while singing the title song, “Secret Place,’’ a capella. Some things you have to just see to believe.

Other Hollywood veterans turning up briefly include Andy Devine, Grady Sutton, Jim Backus and B.S. Pully. I feel relatively confident that no other movie has name-checked Brenda Joyce, Patricia Collinge and Martin Gable while also paying homage to Fellini. Myra’s comments in the novel about how she would show her appreciation of James Craig are sadly not carried over to the movie, but I suspect that had more to do with Fox’s very busy legal staff than good taste.

I’d like to give a big shout-out intrepid TCM programmer Millie De Chirico for championing my campaign to get the network to finally show “Myra Breckinridge.” Understandably, it’s had very little TV exposure, exclusively on cable channels, most recently on the old Fox Movie Channel a decade or so ago. It originally carried an X rating, just like Fox’s “Beyond the Valley of the Dolls,’’ which opened in New York the same week. Both were later re-rated R — a very hard R. The “Breckinridge” premiere will appropriately follow TCM’s most excellent three-LGBT-film tribute to the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising.

Perhaps it will inspire someone in Hollywood (Ryan Murphy? The Wachowskis?) to remake a novel that was literally unfilmable 49 years ago, hopefully with a trans actress. I’d be even more interested in a film or TV version of Vidal’s forgotten and even wilder 1973 sequel “Myron,’’ which has Myron and Myra battling over control of their body while trapped inside a fictional Myra Montez movie being filmed at MGM in 1948. Even Richard Nixon has a cameo.

For more about the film, here’s a link to Frank Miller’s exhaustive study of its tortured production history on the TCM website. Also, three old New York Post “Myra” pieces: my 2004 interview with Welch when the film first appeared on DVD (it was reissued last year), my 40th anniversary appreciation and my report on her no-holds-barred 2012 Q&A with Simon Doonan at Lincoln Center. The 2001 “AMC Backstory’’ episode embedded below includes additional hilarious comments from Reed, who loathes the film.

The clips, in order of appearance:

- “Stowaway” (1934) — Shirley Temple, Philip Ahn.

- “Hell and High Water’’ (1954) — Atomic blast

- “One Million Years B.C.’’ (1966) — Welch, John Richardson

- “Charley’s Aunt’’ (1940) — Jack Benny, Reginald Owen, James Ellison

- “Hell and High Water’’ — 2 more clips

- “Jesse James’’ (1939) — John Carradine, Tyrone Power (2 clips)

- “Hell and High Water’’ — another clip

- “Jesse James’’ — Carradine

- “Seven Sinners’’ — Dietrich (only non-Fox clip, licensed from Universal.

- “Kiss of Death’’ (1947) — Richard Widmark

- “Great Guns’’ — Laurel and Hardy (2 clips)

- “Dragonwyck’’ (1947) — Vincent Price

- “Great Guns”

- “Heidi’ (1937

- “Mr. Moto’s Gamble’’ (1937) — Peter Lorre, Jayne Regan

- “Unfaithfully Yours’’ (1948)?

- “The Mark of Zorro’’ (1939) — Power, Basil Rathbone“

- “That Night in Rio’’ (1941) — Carmen Miranda

- “Sun Valley Serenade’’ (1941) — Glenn Miller (two clips)

- “All About Eve’’ — Gregory Ratoff, George Sanders.

- “Zoo in Budapest’’?

- “Sun Valley Serenade’’ — Nicholas Brothers, Dorothy Dandridge

- “Great Guns’’ again

- “The Gang’s All Here’’ — Chorus, two clips.

- “Something’s Gotta Give (1963)’’ — Monroe, outtake from unfinished film.

- “Tin Pan Alley’’ (1941) — Alice Faye, John Payne

- “Margie’’ (1945) — Jeanne Crain, Glenn Langan

- “Bus Stop’’ (1956) — Don Murray

- “Pigskin Parade’’ (1936) — Judy Garland, Tony Martin

- “Prince Valiant’’ (1954) —Battering ram

- Unidentified

- “Great Guns’’ — Sheila Ryan, Edmund McDonald.

- The Rains of Ranchipur’’ — Dam bursting

- “Folies Bergere’’ — Chorines in rain

- “State Fair’’ (1945) — Dana Andrews, Jeanne Crain

- Unidentified — glider

- “Hell and High Water’’

- “Dante’s Inferno’’ (1935) — Lost souls.

- “Everybody Does It’’ (1949) — Celeste Holm, Charles Coburn

- “Tonight We Sing’’ (1953) — ballerina Tamara Toumanova

- “Great Guns’’ two more clips, yet again

- “Moon Over Miami’’ (1940) — Charlotte Greenwood

- “Roxie Hart’’ (1942) — Ginger Rogers

- Unidentified — glider

- “Pride of St. Louis’’ (1951) — Dan Dailey, Joanne Dru

- “Under Two Flag’’ (1935) — Victor McLaglen, Ronald Colman, Rosalind Russell

- “Pride of St. Louis’’

- “It Had to Happen’’ (1935) — George Raft, Russell

- Yep, “Great Guns.’’

- “Blood and Sand’’ (1939) — Laird Cregar

- “Bright Eyes’’ (1934) — accident witnesses

- “Blood and Sand’’

- “Under Two Flags’’ (Claudette Colbert, Colman)

- “Mr. Moto’s Gamble’’

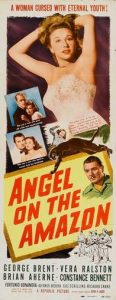

Former Warner star George Brent gets top billing in “Angel on the Amazon” (1948, repeated Feb. 7), but the byzantine story is built around Ralston, a mysterious woman he meets in the jungle when she rescues him — and the other occupants of the plane he crashed in the jungle during a storm — from headhunters.

Former Warner star George Brent gets top billing in “Angel on the Amazon” (1948, repeated Feb. 7), but the byzantine story is built around Ralston, a mysterious woman he meets in the jungle when she rescues him — and the other occupants of the plane he crashed in the jungle during a storm — from headhunters.

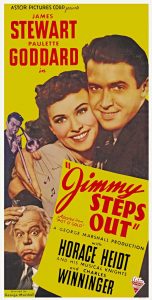

“James Stewart acknowledges that TV has brought out a couple of ghosts he would just as soon forget,’’ Pryor wrote in The Times. “He first saw television in a New York hotel room in 1950. Having tuned in a ‘jumble of noise and confused action,’ he was happily thinking ‘if this is television, Hollywood has nothing to worry about, until suddenly I recognized myself on the screen. It took me some time to figure out it was ‘Pot O’Gold,’ a picture that I had done before going into the Army and had never seen.’’

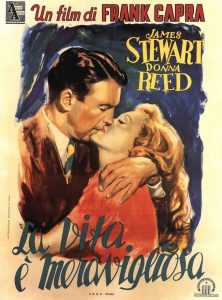

“James Stewart acknowledges that TV has brought out a couple of ghosts he would just as soon forget,’’ Pryor wrote in The Times. “He first saw television in a New York hotel room in 1950. Having tuned in a ‘jumble of noise and confused action,’ he was happily thinking ‘if this is television, Hollywood has nothing to worry about, until suddenly I recognized myself on the screen. It took me some time to figure out it was ‘Pot O’Gold,’ a picture that I had done before going into the Army and had never seen.’’ Stewart continues in The Times piece: “But it’s not all bad. ‘It’s a Wonderful Life,’ which I made with Frank Capra after we both got out of the army, has been on television many times. I’ve seen it and I think is very well adapted to TV. I’ve had more comment and favorable reaction to this picture on television ten years after it was made than when it was first shown in theaters. It seems to please audiences more on a little screen.’’

Stewart continues in The Times piece: “But it’s not all bad. ‘It’s a Wonderful Life,’ which I made with Frank Capra after we both got out of the army, has been on television many times. I’ve seen it and I think is very well adapted to TV. I’ve had more comment and favorable reaction to this picture on television ten years after it was made than when it was first shown in theaters. It seems to please audiences more on a little screen.’’