The Museum of Modern Art’s wonderful “Republic Rediscovered” series of restorations co-curated by Martin Scorsese has been an opportunity to acquaint myself not only with films I’ve never seen but performers I’ve only been vaguely aware of.

Vera Hruba Ralston, the queen of the Republic lot, is probably best known as one of John Wayne’s many leading ladies, but on Saturday I caught her in a couple of bonkers ’40s vehicles that were cooked up for her. A Czech ice skater, Vera Hruba was signed as Republic’s answer to Sonia Henie, but then she married studio honcho Herbert Yates and was rechristened with a new last time reportedly taken from a cereal box and turned into a dramatic star.

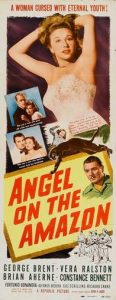

Former Warner star George Brent gets top billing in “Angel on the Amazon” (1948, repeated Feb. 7), but the byzantine story is built around Ralston, a mysterious woman he meets in the jungle when she rescues him — and the other occupants of the plane he crashed in the jungle during a storm — from headhunters.

Former Warner star George Brent gets top billing in “Angel on the Amazon” (1948, repeated Feb. 7), but the byzantine story is built around Ralston, a mysterious woman he meets in the jungle when she rescues him — and the other occupants of the plane he crashed in the jungle during a storm — from headhunters.

The smitten Brent and his chic doctor friend (a quite bemused Constance Bennett) encounter Ralston again in Rio de Janiero (courtesy of stock footage lifted from “Flying Down to Rio,” which also turns up in Republic’s “Brazil,” available on Blu-Ray). Despite the aging Brent’s best romantic efforts, Ralston remains skittish, especially after she glimpses a man from her past (Fortunio Buonanova), who fills Brent in with a tragic flashback after she flees the country.

The film’s third act takes place in Pasadena, where Brian Aherne (in old-age makeup), who Brent believes is Ralston’s father, narrates an even more ridiculous flashback featuring Ralston in a dual role. Not that anyone who had glimpse at the film’s ads or posters wouldn’t know she was “cursed with eternal life.”

Even Garbo would have a hard time pulling off this risible premise, and Ralston was no Garbo, even though Hungarian emigre director John Auer, a Republic workhorse, keeps her dialogue — delivered in a sometimes inscrutable accent — to an absolute minimum and just lets the audience drink in her beauty.

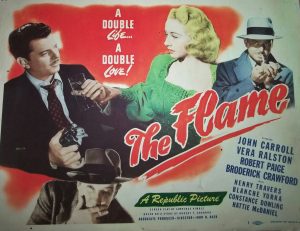

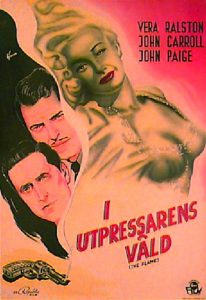

Poverty Row stylist Auer also helmed the equally entertaining, if utterly preposterous, “The Flame” (1947, Feb. 7) which casts Ralston (some of whose copious dialogue appears to be dubbed) as a French nurse who assists her American boyfriend (John Carroll, a former Clark Gable standby at MGM who generally rode the ranges for Republic) in a torturous scheme to inherit his half-brother’s millions.

Ralston works as a nurse to the half-brother (erstwhile Universal leading man Robert Paige), who is dying of an unspecified disease and seduces him into what’s supposed to be a very short marriage. But then of course she falls in love with her new organ-playing husband. Further complications are provided by a blackmailer (Broderick Crawford, who’s a hoot) mooning over his nightclub singer girlfriend (Constance Dowling) who takes a shine to Carroll.

The cast also includes Blanche Yurka as Paige’s aunt, who is justifiaby suspicious of Ralston’s motives, and Henry Travers as his doctor uncle, on hand to try to sell the improbably happy ending to audiences. “The Flame” also benefits from some nifty second-unit footage shot in New York City, where Carroll’s character lives on Central Park South.

MoMA offers two more glimpses of Ralston at the beginning and the end of her career. Repeating on Feb. 7 is Republic house director Joe Kane’s “Accused of Murder” (1956), released three years before the studio’s demise. Ralston plays the title character, a nightclub chanteuse that police detective David Brian tries to clear of killing her admirer, shady lawyer Sidney Blackmer. Filmed in an especially lurid version of Republic’s Trucolor and their widescreen process Naturama, the excellent cast includes a scene-stealing Dolores Gray as a key witness, Warren Stevens as a vicious mob hitman, a clean-shaven Lee Van Cleef as Brian’s junior partner and Elisha Cook Jr. as a weaselly informer. George Sherman’s “Storm Over Lisbon” (1944), described by MoMA as Republic’s budget version of “Casablanca” features Ralston in her dramatic acting debut opposite Richard Arlen and Erich von Stroheim. It’s showing on Feb. 9 and 14th.

I was even less familiar with the work of William Elliott, as he was known during a Republic interregnum between a pair of stints for Monogram/Allied Artists where he billed as “Wild Bill.” (He used “William” again for a handful of AA police thrillers at the end of his career). During the ’30s, as Gordon Elliott, he appeared in dozens of often unbilled bit parts mostly at Warner Bros., briefly dancing with another man as a winking Al Jolson quipped “Boys Will Be boys” in “Wonder Bar” (1934).

Elliott was past 40 when he made western expert R.G. Springsteen’s delightful “Hellfire” (1949), acting with a lack of artifice reminiscent of Gary Cooper as a soft-spoken but tough gambler who decides to build a church as a tribute to the preacher who dies taking a bullet meant to Elliott.

His faith is tested when he crosses paths with sexy outlaw Doll Brown (noir icon Marie Windsor, who’s excellent), whose real name is Mary Carson and is searching for her younger sister. Doll has a price on her head for her husband’s murder and she is being hunted for the bounty by the husband’s brothers (Jim Davis, a year after “Winter Meeting” with Bette Davis, is the leader).

What makes the plot unusual is that she is also being sought by marshal Forrest Tucker, who is married to Doll/Mary’s sister and is also Elliott’s best friend. Only Elliot realizes that they are in-laws, but helps Doll when she assumes yet another identity, as saloon singer Julia Gaye, to fool Tucker. Things get really complicated when Tucker falls for his sister-in-law, who encourages his attentions to make Elliott jealous. Well, I said it was complicated. But it works.

“Hellfire” was photographed in Trucolor process, which looks fantastic in this restoration. Windsor is ravishing whether she’s wearing leather or lace, and is more than up to the dramatic demands of the climax, when her late husband’s brothers storm the jail where she’s being held. Elliott handles action and dialogue scenes with such seemingly effortless aplomb that you wonder how he would have fared as a star at the majors studios. “Hellfire” is being repeated on Feb. 6 and Feb. 13 and offers elements of interest even for non-western diehards.

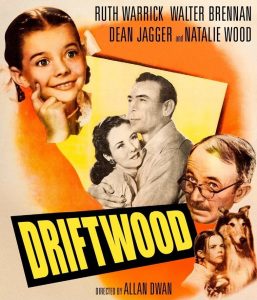

I also very much liked my first viewings of a couple of Republic’s family films: Allan Dwan’s religion-suffused “Driftwood” (1947, repeated Feb. 8), with an extraordinary performance by Natalie Wood as a six-year-old orphan experiencing civilization, including a spotted fever epidemic, for the first time; and Kane’s “Trigger Jr.” (1950, repeated on Feb. 10), an irresistible Roy Rogers vehicle in gleaming Trucolor that packs a solid plot, three songs and several circus acts into just 68 minutes.

Also highly recommended is the only high-profile film in the series, another family film which I’d somehow never gotten around to seeing. Lewis Milestone’s sublime “The Red Pony” (1949, repeating Feb. 12), is an example of Republic’s post-war ambitions to lure the carriage trade as the majors loosened their grip on theaters in the wake of a court order. It has Robert Mitchum, Myrna Loy, genuine three-strip Technicolor, a script by John Steinbeck, music by Aaron Copland and one of the most frightening climaxes I’ve ever seen in a movie.

The first screening of “Trigger Jr.” was accompanied by an hour’s worth of clips from beautifully restored Republic features and serials, some quite obscure indeed (like “Rosie the Riveter”). It was introduced by Andrea Kalas, archive director at Paramount Pictures, present owner of the Republic library, whose team is to be highly commended for the labors on hundreds of them. The splendid series continues through Feb. 15, then resumes again in August.