Tonight’s landmark in the history of theatrical motion pictures on television is one of my favorites. WCBS, the once-mighty CBS flagship, became the first New York City television station with (nearly) 24-hour broadcasts, showing movies from 11:30 pm till dawn (more or less) beginning 55 years ago.

Extended hours were nothing new for some west coast stations, which began offering film series with names like “Swing Shift Theater” as early as the 1950s. Even the CBS-owned station in Philadelphia somehow beat WCBS to the punch with multiple entries of “The Late Late Show” on the same night.

WCBS had offered the longest broadcast day of any New York City station since the 1951 introduction of “The Late Late Show,” which originally aired only on Friday and Saturday nights, despite the fact that the city had a substantial population of shift workers who got off work in the middle of the night (including yours truly, who got off work around 2 am at both The New York Post and the Bergen Record at various points in the 1970s).

Thanks to libraries full of relatively short films sourced largely from Poverty Row studios, Channel 2 managed to sign off by 2 a.m. on most “Late Late Show” nights in the early years. A notable exception occurred on New Year’s Eve 1952, when midnight coverage of the ball drop in Times Square was followed at 12:05 a.m. by the all-star epic “Forever and a Day,” which was repeated at 2 a.m. Presumably, the station was on the air until around 4.

Running times got much longer after WCBS began showing hundreds of newly-acquired films from MGM in December 1956 and Warner Bros. the following month. You might have guessed that Channel 2 would call it a night after the April 5, 1957 debut of the massively long MGM musical “The Great Ziegfeld” (1936) on “The Late Show.” But no, it was followed at 2:30 a.m. by “Key Witness.” (Columbia, 1946). Then there was five minutes of “The Late Late News” at 3:45 and another five of “Give Us This Day,” with signoff finally arriving just before 4 again.

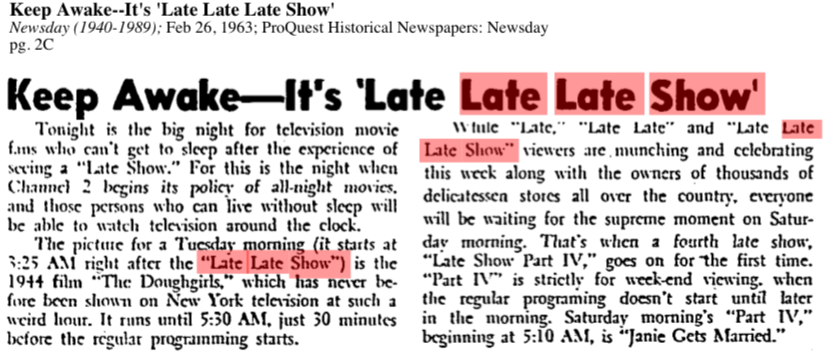

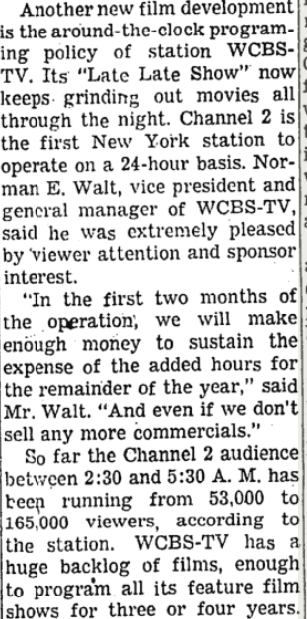

The 1963 expansion of “The Late Late Show” was timed to coincide with the 12th anniversary of “The Late Show.” according to an announcement that was covered in the Long Island newspaper Newsday. At the time, New York City was in the midst of a 111-day newspaper strike and lockout that shut down all seven mainstream papers, so this historic event didn’t receive as much coverage as it much have otherwise. (Except on Channel 2, which had began running daily reminders of the upcoming schedule on its evening news. I vividly recall noticing with astonishment that that the Fox musical “Hello, Frisco, Hello” was airing very either very late one night or very early one morning.)

At the time, Channel 2 had something called called “College of the Air” airing at 6 a.m. on weekdays, so on most nights the final “Late Late Show” would end somewhere in the vicinity 5:30, still followed by news, “Give Us This Day” and signoff. Vintage TV listings I’ve studied don’t precisely document this, but veteran viewers have written that sometimes as few as five minutes elapsed before Channel 2 signed on again, followed by “Give Us This Day” and news. “College of the Air” did not air on Saturday and Sunday and “Sunrise Semester” (which aired at 6:30 weekdays) did not start until 7:30 a.m. on weekends, so “The Late Late Show” often ran past 7 a.m. on Saturday and Sunday mornings, at least from 1963 to around the end of the decade.

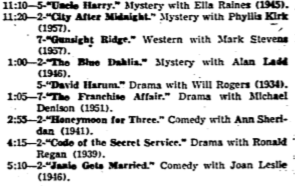

WCBS had a substantial number of short pre-’48 B features (60 minutes, give or take) from Warner Bros., Paramount and Universal under license at this point, so in the very earliest years of its all-night broadcasting, they often offered “The Late Late Show,” “The Late Late Show II” and “The Late Late Show III” on weeknights. (“College of the Air” was quickly given the heave-ho, allowing the broadcast day to begin with “Sunrise Semester” at 6:30). Depending on the lengths of films, on some Friday and Saturday nights, there was even “The Late Late Show IV,” as it was identified in the New York Times listings. I’ve seen some of the latter starting as late as 6:05 a.m. on a Sunday morning, which would normally qualify as a Sunday listing. The Times carried as part of the Saturday night schedule.

During this period, WCBS often showed as many as four movies on Saturday afternoons when there weren’t sports preemptions — hour-long features at 2, 3 and 4 o’clock, followed by “Life of Riley” or “Love That Bob” at 5 and a 75-minute Saturday edition of “The Early Show” (it ran 90 on weekdays). So there were as many as eight movies on those days with a total running time (including commercials) of approximately 11 1/2 hours (or nearly half the broadcast day).

Of course, this couldn’t last in the long run. The increasing average length of films that WCBS showed in late-night, with ever-larger number of commercials, reduced the number of films that could be shown. There were also CBS network incursions into late night, beginning with some late-night NFL games on Saturday nights in the late ’60s. CBS pitted “The Merv Griffin” versus “The Tonight Show” in 1969, which pushed “The Late Show” to a 1:10 a.m. start. That was followed in 1972 by the ever-expanding “CBS Late Movie” (which included off-network reruns of shows like “M*A*S*H,” “Kojak” and “Columbo”) and was renamed “CBS Late Night,” the unfortunate “Pat Sajak Show” (1989-1990) and “Crime Time After Prime Time.”

For some of us, the ultimate indignity came when CBS repurposed the “Late Show” name for David Letterman’s talk show in 1993, which was followed by another CBS talk show called (oh, the horror) “The Late Late Show.” By that point, the uber-cheap “CBS News Overnight” had reduced CBS’ once-vaunted library to a few minor Warner titles like “Hotel” and made-for-TV films that were played off on Friday nights. The station’s Saturday nights were already given over to the likes of “American Gladiator,” the weekend edition of “Entertainment Tonight” and infomercials.

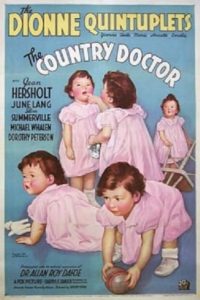

But there was this great and glorious period when I would often get up in the middle of the night to watch movies on WCBS. I spent half a century ruing the morning during high school that I slept through the alarm on the night they aired “The County Doctor” (1936), a Fox epic starring the Dionne Quintuplets. It remained stubbornly unavailable for decades, finally arriving on DVD a few years ago (after I suggested it to the Fox Cinema Archives). When I was a teenager, it was reassuring to know there was a place I could watch “Steel Against the Sky” (WB, 1941), even if it was at 4:45 a.m. in the morning and interrupted by commercials. It doesn’t exactly live up to that title, either, but it does show up from time to time on TCM.

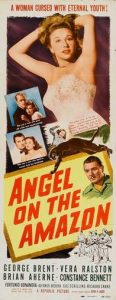

Former Warner star George Brent gets top billing in “Angel on the Amazon” (1948, repeated Feb. 7), but the byzantine story is built around Ralston, a mysterious woman he meets in the jungle when she rescues him — and the other occupants of the plane he crashed in the jungle during a storm — from headhunters.

Former Warner star George Brent gets top billing in “Angel on the Amazon” (1948, repeated Feb. 7), but the byzantine story is built around Ralston, a mysterious woman he meets in the jungle when she rescues him — and the other occupants of the plane he crashed in the jungle during a storm — from headhunters.